The Canal, or rather the Canals (the Willebroeck Canal and the Charleroi Canal), have had a profound impact on the landscape and spatial structure of Brussels, influencing its urban development and socio-economic context and enriching its industrial architectural heritage.

The Senne: the origins of Brussels

The valley of the Senne, the river that runs through Brussels from southwest to northeast, is the birthplace of the city. Brussels first emerged here around the 10th century on an island called the Ile Saint-Géry, in the marshy area around the furthest navigable point on the Senne. This area was a transhipment point for goods at this time. Further upstream, the Senne’s numerous meanders, due to silting and low relief, made it very difficult to negotiate, so it was around the Ile Saint-Géry that a series of water mills were built and that the main medieval communication routes – both by water and by land – converged. It was here, too, that merchants and craftsmen set up shop, and that the first religious and military establishments grew.

From the 13th century, Brussels was established as an important industrial city. The river was the main source of primary energy, driving the numerous mills that were built along its banks. Hydraulic projects were used for flood attenuation, the creation of fish ponds and the irrigation of areas away from the flood zone. The Senne facilitated the development of the textile and food industries. It was the main route linking Brussels to the economic hub of Antwerp and to the North Sea, via the Scheldt.

However, it was also used for the discharge of domestic and industrial waste water, and became little better than an open sewer: Brussels’ sewerage network was not created until the second half of the 19th century.

The Willebroeck Canal (1551-1561)

Brussels’ initial economic boom was founded on drapery, tapestries, lace and similar goods. The port was developed in the area of what is today the Place Sainte-Catherine. In this district, many roads still bear names that evoke this river-based past of commerce and craftsmanship (such as Quai aux Briques (‘Brick Wharf’), Quai du Commerce (‘Commercial Wharf’) or Quai à la Houille (‘Coal Wharf’)), despite the fact that the docks have long since been filled in. But although trade took place by waterway, the uncertain course of the Seine and the rights of use of the towns and cities situated on it proved an obstacle to development.

In 1477, Mary of Burgundy authorised the construction of a Canal with a different route from that of the Senne. However, it took nearly a century and the granting of a new authorisation by Charles V for work to begin on what would become the Willebroeck Canal.

Built between 1551 and 1561, the Willebroeck Canal connected Brussels to Antwerp in 30 km (one to two days by boat) – significantly less than the 120 km of the meandering Senne (eight or more days by boat). In Brussels, warehouses, shops, factories, hotels and other buildings were constructed on the new canal’s quays.

The Charleroi Canal (1830-1870)

The 18th century saw the emergence of new industries such as earthenware production, carriage-making and printing. Some factories were built in the city centre, while others grew up further along the central axis of the Senne valley, in places such as Anderlecht and Molenbeek. As urban and commercial growth gathered pace, the arrival of raw materials, including coal, became crucial.

In 1827, during the period of Dutch rule, construction work began on a canal linking Brussels to Charleroi and the Hainaut mining area. This was opened in 1832. The Willebroeck Canal, meanwhile, was deepened to accommodate vessels of a greater tonnage. The junction of these two waterways was created where Place de l’Yser is located today.

The opening of the Charleroi Canal enabled coal to be brought in on a massive scale and underpinned a spectacular industrial, demographic and urban boom in Brussels, which became the country’s leading region for industrial employment. The mechanisation of industry led to the appearance of foundries and engineering and metalworking companies. This in turn accelerated the development of the railway network, which had the effect of dividing up the urban landscape.

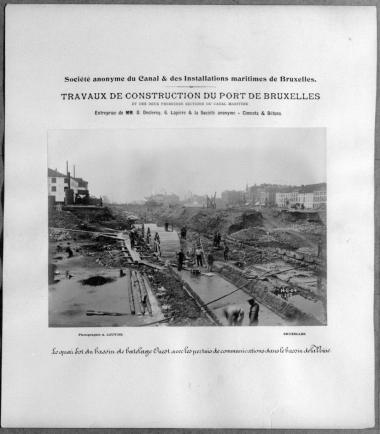

Brussels as a sea port (1900-1922)

In the late 19th century, the rail network reached saturation point. Gradually, the idea gained ground of turning Brussels into a sea port. This was done by building ever more extensive and deeper port facilities to accommodate not just river barges, but seagoing vessels too.

The implementation of this idea in the early 20th century transformed the city. The three main docks, Gobert, Béco and Vergote, were opened in 1922. The outer harbour, downstream, was opened in 1939. To ensure a straight-line connection with the Charleroi Canal, the bed of the Willebroek Canal was moved 60 m to the west, so that the Canals leading north and south now met where the Pont Sainctelette is located today.

The opening of this sea port influenced the city’s development. The disused docks of the old port, in the Sainte-Catherine area, were gradually filled in. A huge industrial complex sprang up on the Tour & Taxis site, including a freight yard, a customs area and warehouses. New sectors grew up to the north and south of the axis formed by the two canals: chemicals, petrochemicals, construction materials, gas works, coking works, cement works and so on. These occupied larger sites than the small and medium-sized family businesses located on either side of the central section of this axis.

Despite the damage of the Second World War, the Port continued to expand northwards. Its infrastructure was modernised again in the second half of the 20th century, with the construction of quays, the appearance of the TIR Centre, the widening of the Canal and the building of new bridges.

Deindustrialisation and urban revitalisation

From the 70s, Brussels, like many other large cities, experienced a downturn in its population as the middle and upper classes moved out to the periphery. Furthermore, having been the country’s main region for manual labour until the late ‘60s, Brussels was hit particularly hard by deindustrialisation: in 40 years, it went from having 160,000 industrial jobs to less than 30,000. Along the Canal axis, logistics gradually replaced industry. Since the turn of the millennium, activity in the Port has provided some 12,000 jobs, and the Canal Area has been home to some 6,000 companies across all sectors. In recent years, some 6.5 million tonnes of goods have passed through the Port every year – the equivalent of over 611,000 trucks.

But all along the line of the Canal, and especially in its central section, deindustrialisation led to the emergence of brownfield sites and the deterioration of the building stock. This phenomenon was coupled with the arrival of lower-income population groups. As a result, the figures for income, employment and many other indicators in some districts were a cause for concern at the time of the creation of the Brussels-Capital Region, in 1989. Since then, the Government of the Brussels-Capital Region and the municipalities concerned have introduced numerous initiatives (such as Neighbourhood Contracts or the Pentagon Development Delegation), including several with support from the European structural funds (ERDF, URBAN, etc.), to help industrial areas undergoing conversion, and then urban areas where development had lagged behind.

These programmes have produced tangible results in many places, including a genuine revitalisation and significant repopulation of the right bank of the Canal, between the waterway and the boulevards of the city centre. However, some districts bordering the Canal which have significant potential, including land for development, are still struggling, and are also contending with Brussels’ current population boom. Among other things, this has led the Government of the Brussels-Capital Region to initiate a Canal Plan, in order to harness local potential to meet needs more effectively.

(*)This text is largely based on the chapters ‘Histoire-Patrimoine’ and ‘Géographie physique-Environnement’ of the atlasCanal? Vous avez dit canal?!État des lieux illustré du Territoire du canal à Bruxelles(‘Canal? Did you say Canal? An illustrated survey of the Brussels Canal Area’) published in 2014 by the Urban Development Agency for the Brussels-Capital Region. This book is available for free download in FR and NL. Given its size (50 Mb), the document opens slowly in browsers. To read it, we therefore advise you to save it to your computer.